A Common Fallacy in the Energy and Climate Debate

The vast majority of the energy and climate debate takes place in the developed world and, understandably, much of this debate is focussed on the developed world itself. However, as clearly shown in the two figures below, the developed world is already of lesser importance when it comes to energy and climate issues and will continue to rapidly lose significance over coming decades.

As shown above, the developed world share of total emissions is projected to fall from 56% in 2000 to only 27% in 2040. The story is very similar for total energy demand in the graph below.

The nature of the energy and climate debate changes completely depending on whether it is viewed from a developed or a developing world point of view. This article will elaborate further on this difference and its implications on the debate itself.

Differing economic growth priorities

In general, the developing world will pursue economic growth at almost any cost while the developed world, for reasons outlined below, has been forced into a mode of just trying to preserve current levels of material affluence and social welfare.

It is obvious why the developing world wants to grow. The average developing world citizen consumes roughly five times less value than the average developed world citizen. A full 2.5 billion people still survive on less than $2/day (an amount of value consumed roughly every 30 minutes by the average developed world citizen). It is therefore no wonder that developing world citizens also want proper housing, cars and the wide range of consumables that people born in developed countries simply take for granted.

As demonstrated by Japan some decades ago (below) and by China more recently, a poorly developed nation can grow very rapidly over an extended period of time through intelligently copying best practices from the developed world. Very rapid catch-up growth can be sustained for decades, but can also slow rather suddenly when a nation runs out of things to copy and has to start innovating. Today, roughly 20% of the world must innovate (developed), while the remaining 80% still has a lot of copying potential (developing).

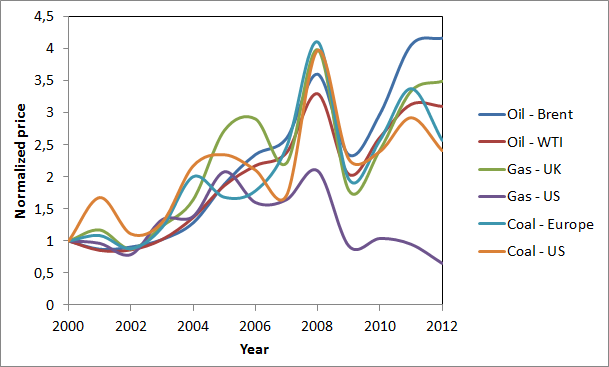

However, the 21st century has brought an additional very important growth challenge to the developed world: expensive energy. Since global fossil fuel prices quadrupled in the seven years following the turn of the century (below), the energy intensive lifestyle that is viewed as standard in the developed world has suddenly become a lot more expensive. Energy costs related to a big home in the suburbs (heating, cooling, appliances and commuting) now take a significant chunk out of the disposable income of the average developed world citizen, not to mention the price inflation effects that rising energy costs have on almost all of the other commodities he so liberally consumes.

Less disposable income means less spending on other things, leading to unemployment and a drop in asset prices. This, in turn, leads to a further drop in disposable income, thereby completing the vicious cycle. Statistics for real median income and unemployment in the US are given below as an example. It is clear that, despite US federal debt doubling since the crisis and the total amount of quantitative easing (money printing) closing in on $4 trillion, the trends are not good. Note that the better-looking U3 unemployment figure is the headline figure, but the SGS Alternate figure is arguably the real figure counting also long-term unemployed people and those who have simply given up looking for work.

Meanwhile, developed world governments are becoming increasingly insolvent. Debt and other unfunded liabilities (Social Security and Medicare) are growing rapidly and will force significant reductions in developed world growth over coming years through reductions in government spending and increases in taxation. The figure below shows one prognosis for the US.

Currently, developed nations (particularly the US) can still use the reputation of their currencies to maintain consumption at a reasonable level. In other words, developed nations can exchange dollar or euro denominated paper assets for real goods and services produced by other nations. The persistent trade deficit of the US given below is a case in point. If the US dollar was not the world reserve currency and we had not just had a 3-decade bull market in government bonds, these persistent trade deficits would have devalued the dollar and forced Americans to substantially cut their consumption many years ago.

It is uncertain how long central banks can keep this highly fragile system stable, but one thing is clear: in the years to come developing world economies will grow and developed world economies will (at best) stagnate. GDP data over the last decade (below) gives a clear example of things to come.

Differing environmental priorities

In spite of the economic challenges described above, developed world citizens are still many times more affluent than developing world citizens. This implies that the developed world has a willingness to pay for benefits such as cleaner air and reductions in other forms of pollution. The sharp reduction in emissions from US coal-fired power plants is given below as an example.

As discussed in a previous article, however, the developing world has very different priorities. Despite pollution levels often reaching truly shocking levels, the developing world still prioritizes economic growth over clean air. For example, it was discussed that non-CO2 externalities in India are viewed to be roughly one order of magnitude smaller than in the US. This is a very important point for developed world citizens to realize. If you were 10 times poorer than you are today, you would most likely also not care that much for pollution from coal power plants as long as it provides the cheap and reliable power necessary for you to better your life.

The case of CO2 is even more complex. If the developing world is unwilling to pay for reducing pollution that has a direct and immediate impact on their daily lives, it is pretty obvious that they are not going to be paying for pollution that will only start having a substantial and clearly attributable impact many years from now. Besides, even though the developing world now emits more CO2 per year than the developed world, they are still far behind when it comes to cumulative emissions. A few examples are given below.

It is therefore clear that all the developed world talk about enormous fossil fuel externalities is purely academic for the part of the world where the majority of fossil fuels is burned. Until the developing world becomes sufficiently rich or the effects of pollution become truly unbearable, economic growth will be prioritized over environmental concerns. This prioritization is fully justified and highly unlikely to change any time soon.

Differing family priorities

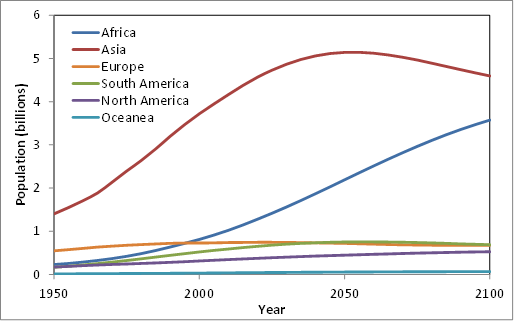

If it was not for immigration, the developed world would be shrinking right now. The population of the developing world, on the other hand, is still growing rapidly (below).

The reasons for these trends are fairly obvious. Developed world citizens have much greater access to education and birth-control. In addition, while a child in rural areas of the developing world is seen as a major asset (another pair of hands on the farm), raising children in the developed world is a great financial burden, especially within the current economic environment.

Current rapid population growth in the developing world can only be slowed by continued economic development and urbanization, a process that will require enormous amounts of cheap, practical and reliable energy. Since a stable population is the first requirement of a sustainable society, economic development in the developing world must be a top priority, thereby implying that this rapid growth in energy consumption should be encouraged and accommodated by the global community.

What does this mean?

People participating in the energy and climate debate should be very careful of always approaching these issues from a developed world point of view. This view is simply not applicable to the part of the world where the most energy is consumed and the most CO2 is emitted. In fact, two short decades from now, the developing world may very well emit triple the amount of CO2 of the developed world.

It is vital that we accept the objective reality that developing world citizens will not prioritize pollution reduction (CO2 and other) over economic growth unless it is very cheap and highly practical. Clean solutions need to come pretty close to a steady, dispatchable coal-fired electricity supply at $0.04/kWh, practical and reliable new cars at $10000 apiece, and direct industrial heat at $0.01/kWh (coal at $70/ton).

Realistically, this implies CCS, nuclear and large hydro for electricity, a great focus on more efficient ICEs and hybrids for transportation and CCS for direct industrial applications. The green dream of solar panels, wind turbines, batteries and EVs quite simply is nowhere close to being able to facilitate rapid developing world growth (see this previous article for example).

In addition, the green dream is still just a dream even in the developed world (non-hydro renewables provide only 3.1% of OECD energy), implying that decades of typically slow trial and error are still required before this largely theoretical world of distributed and intermittent electricity generation, intercontinental super-grids, smart demand management and large scale energy storage can become a reality. The developing world doesn't want slow trial and error, it wants proven systems that can drive rapid growth on a very large scale right now.

Unfortunately, the developed world has neglected CCS and is abandoning nuclear, thereby leaving renewables as the only clean energy alternative that can be copied by developing nations. Given this state of affairs, it should come as no surprise that traditional energy sources accounted for fully 96.1% of the non-OECD energy consumption increase from 2011 to 2012 - a value very similar to the 96.5% average over the past 5 years.

...

Yes, the green dream is ideologically extremely attractive, but, as this article has hopefully demonstrated, it is simply not compatible with billions of developing world citizens flocking to megacities in search of higher living standards. The premature pursuit of this dream will do little other than sustain the rapid increase of CO2 emissions in the developing world while further worsening the already highly fragile economic situation in the developed world. There really is no need to make things so hard for ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment